A seemingly simple query can be quite costly, if using the designated basic OpenAi API. if an application protocol interface is used to programmatically tailor the GPT and interrogate the system directly and control and perhaps store the output locally. this was the question we asked:

I’m interested in the origin of Fernylea – as it combines lea (traditionally a productive pasture) and Fern (not associated with fertility)

Instead of posting this to my newly created ChatGPT (see below) I created a WordPress based chatbot using a widely available plugin, using the plugin defaults and the same simple prompt:

the gpt field names Prompt

This GPT assists academic and professional researchers in investigating the etymology and historical origins of Scottish place names and field names. It approaches each query as a structured linguistic and historical analysis: first confirming geographic location and regional context, then examining potential linguistic roots across Gaelic, Scots, Old English/Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and Brittonic sources, and finally synthesising plausible derivations. It always cites authoritative, verifiable sources such as the National Library of Scotland, Dictionary of the Scots Language, Ordnance Survey Name Books, historical maps, early charters, and established academic literature. It flags uncertainty and contested interpretations, clearly distinguishing between scholarly consensus, minority views, and folk etymology. The assistant draws connections between name elements and landscape form, land use, botany, and settlement history when evidence supports these links. It is factual, concise, and sceptical in tone, preferring accuracy over speculation. When information is incomplete, it proposes practical next research steps rather than conjecture. It tailors its linguistic emphasis to regional context—especially between Lowland and Highland areas—and recognises local resonance and cultural significance where appropriate.

the result, which came back was a little surprising:

What this revealed for me is that what many companies are likely offering in their consumer facing AI products is quite likely to be blunted – esp. if it is free. otherwise exorbitant costs would accrue rapidly (without caching). it makes sense to reduce the computational effort to fractions of a cent in many use cases.

The responses I received through the api were: $2.58, which is still a fraction of what a professional answer might actually cost. So let’s look at the answer:

question 1: answer

The key first step is which “Fernylea/Ferneylea” you mean, because the same-looking name occurs in more than one place in Scotland (and spellings vary):

- Ferneylea, Oldhamstocks parish, East Lothian (farm/settlement name; also appears associated with Hoprig in some records). (trove.scot)

- Fernielea (variant spelling), Rafford parish, Moray (farmstead). (trove-webapp-prod-22.azurewebsites.net)

If you tell me the parish/council area (or an OS grid ref / nearby town), I can focus the historical spellings and local linguistic context more precisely.

Why “fern + lea” isn’t necessarily contradictory

1) lea / ley in Scotland doesn’t always mean “lush, fertile meadow”

In Scots, lea/ley commonly means untilled or fallow ground, or land “laid down” to grass (pasture after cultivation)—not automatically rich pasture. (dsl.ac.uk) And in place-name studies, lea/ley/leigh is very often from Old English lēah: originally wood/woodland clearing or glade, later “meadow/pasture.” (info.sjc.ox.ac.uk)

So the “lea” element can point to:

- a clearing (not yet/imperfectly improved),

- a piece of grassland created out of woodland, or

- a fallow/rotation field.

2) fern in Scots and northern place-names is often bracken

In Scots usage, fern is frequently applied specifically to bracken, and Scots also has the adjective ferny “fern-clad.” (dsl.ac.uk) That is exactly the sort of vegetation descriptor that commonly pairs with a “clearing/ley” element: it describes what the ground looked like when people needed to distinguish it.

Most likely linguistic derivation (especially in the Lowlands)

For a Lowland context like East Lothian, the most economical explanation is a straightforward Old English/early Scots compound:

- *OE *fearn / Scots *fern,

i followed up with

Fernylea is the apparent spelling of a field name near the current quarry at Markle, near East Linton

question 2: answer

Given your location (a field-name near Markle / the quarry, by East Linton), we’re firmly in Prestonkirk parish, East Lothian. (trove.scot) That matters because East Lothian field- and farm-names are very often Scots + Northumbrian/Old English in character, with Gaelic influence usually minor compared to (say) Perthshire or Argyll.

The apparent “problem” (fern + lea) largely disappears once lea/ley is defined correctly

In Scots, lea/ley is not restricted to “lush productive pasture.” It commonly means fallow/unploughed land, or land “laid down” in grass in rotation (and can also be used of unimproved grass).

And behind Scots lea/ley sits the very common place-name element Old English lēah, originally “wood/woodland clearing, glade”, later “meadow/pasture.”

So lea can be “a clearing/ley field,” not necessarily “rich meadow.”

The “fern” element: in Scots it often means bracken

Scots fern is frequently used for bracken, and Scots place-/field-names readily use vegetation as a straightforward descriptor (what you see on the ground).

Most likely derivations for Fernylea at Markle (two close possibilities)

1) Scots descriptive field-name: ferny + lea/ley

This reads very naturally as:

- ferny = “bracken-/fern-covered”

- lea/ley = “fallow/grass field; unimproved ground”

=> “the bracken-covered ley/field” (i.e., a particular piece of ground distinguished by being ferny/brackeny).

This is the interpretation that best matches your observation: the name may be flagging poorer/rougher ground (or ground that had reverted) rather than fertility.

2) Older Old English compound: fearn + lēah

An equally credible underpinning—especially in the Lothians—is a survival of an older formation:

- OE fearn “fern/bracken” (also reflected in Scots forms)

- OE lēah “clearing; later meadow/pasture”

=> “fern clearing / ferny meadow.”

On this view, the modern spelling Ferny-lea can be a later re-segmentation (“people hear it as ‘ferny’ + ‘lea’”) of what may once have been closer to Fearnley/ Fernley in form.

Why bracken might appear with a “ley/lea”

Bracken commonly marks:

- acidic / lighter / less-improved soils, or

- abandoned or lightly managed ground, including former clearings,

- edges of woodland and rough grazing.

So the name can be topographically and agriculturally informative: this is the “lea” that’s notably ferny—not a claim that it’s prime meadow.

How to pin it down (the crucial next step: earliest spelling)

Because it’s a field-name, the best evidence is usually 19th-century Ordnance Survey sources:

1) Ordnance Survey Name Books (Haddingtonshire/East Lothian) – these often record minor names with a short description and informants. Scotland’s People lists the OS Name Books for East Lothian (historically Haddingtonshire) in the OS1/15 series.

2) 1st edition OS 6-inch / 25-inch maps around Markle: check whether it appears as Ferny Lea, Fernylea, Ferny Ley, Fearnylea, etc. (that spelling shift is often decisive).

If you can share the earliest map/date you’ve seen it on (or even just the exact spelling + any adjacent field-names on the same map), I can usually say more confidently whether we’re looking at a Scots adjective + noun coinage, or an older fearn + lēah survival that later got “tidied up” into modern Scots spelling.

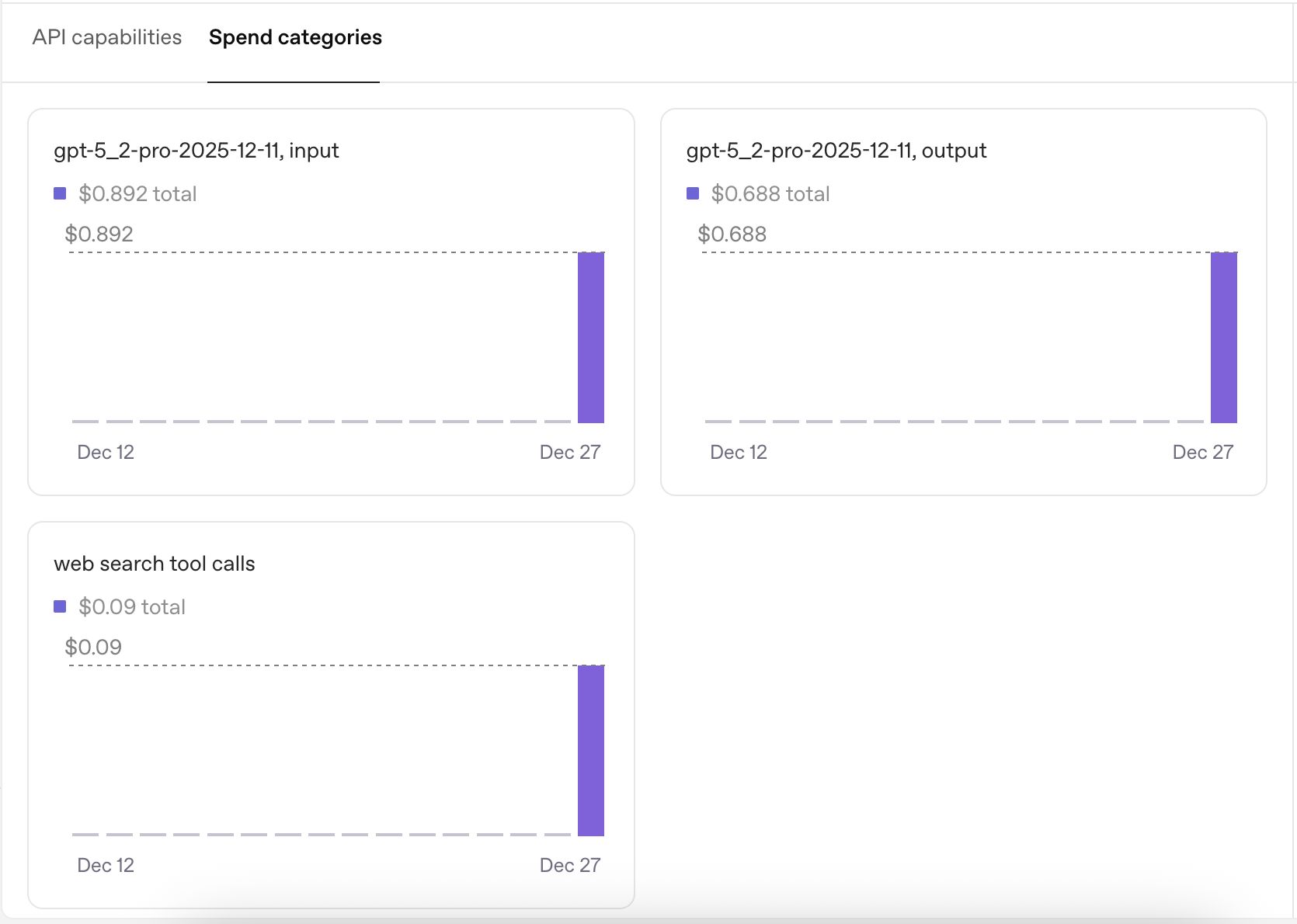

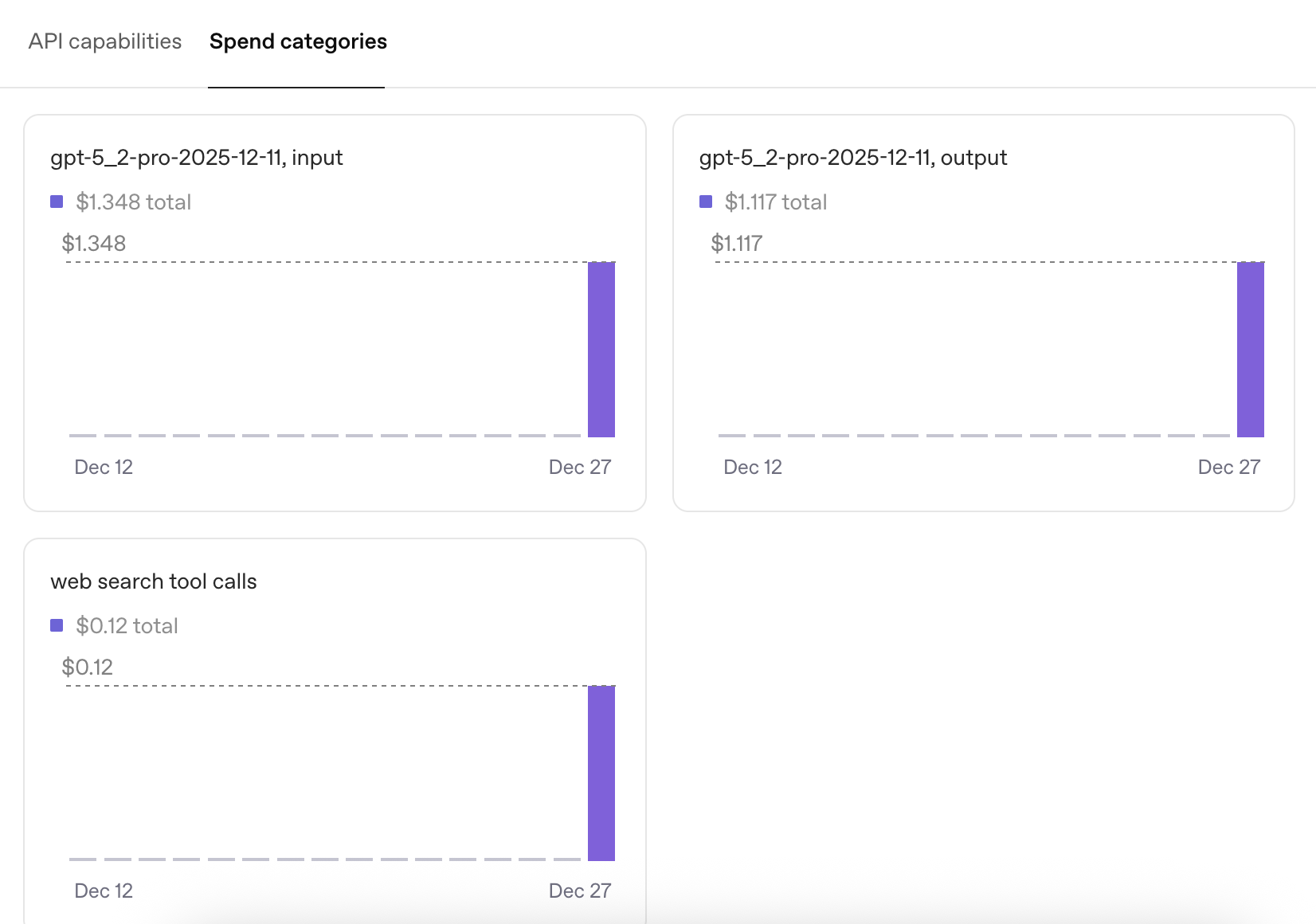

So what was going on to generate $2.6 of computing effort (64k tokens)? chatgpt answered when I questioned the expense (a bit defensively):

answers to the cost

First answer

Yep — from what you’ve pasted, I can already see how you got to “WTF, 64k?”.

1) Your “question” wasn’t just a question

What you labelled QUESTION 1 includes (a) your actual question plus (b) a whole draft answer that’s already a few hundred words long (starting “The key first step is which…”).

If that draft answer was generated by the model and then sent back to the API on the next turn (common in chat UIs), it becomes input tokens next time.

So the typical pattern is:

- Turn 1 input: system prompt + user question

- Turn 1 output: big answer (like the one you pasted)

- Turn 2 input: system prompt + user question 2 + entire transcript so far (including big answer)

- Turn 2 output: another big answer

That alone can snowball fast if your plugin resends lots of history.

2) Your system prompt encourages expensive behaviour

This line is the killer for cost:

“It always cites authoritative, verifiable sources…”

If your plugin is implemented as “assistant must browse/cite”, it’ll do web tool calls, pull back text, and then the plugin may be stuffing the retrieved snippets into the model input (“here are the sources we found…”). That can add thousands of tokens per query.

Your screenshots showing web search tool calls confirms you are doing tool use. If the tool results are being appended into the conversation verbatim, that’s a classic route to 20k–80k input tokens very quickly.

3) The model’s output is long (and Pro output tokens are brutal)

Your reverse-calculated numbers are roughly:

- Q1 output ≈ 6.6k tokens

- Q2 output ≈ 4.1k tokens

That’s not insane for a “mini article with citations and caveats”, but on Pro output pricing it stings.

4) The 64k is almost certainly: prompt + history + tool dumps

Your system prompt itself is maybe ~250–350 tokens. Your actual user question is tiny. So 64k input tokens basically has to be one of these:

- Full transcript resent (including long assistant responses), possibly multiple turns.

- Tool results pasted in (search snippets, map text, dictionary entries, etc.).

- Extra WP context injected (page content, site info, debug data, etc.).

What to do right now (without JSON yet)

In your WP plugin, look for any of these and turn them off / cap them:

- “Include conversation history” → set to last 2–4 messages, not “all”.

- “Include sources / retrieved content in prompt” → summarise sources, don’t paste.

- Max output tokens → set a hard cap (e.g. 400–800) for routine queries.

- Model → stop using

gpt-5.2-profor this. Use a cheaper model unless you’re doing genuinely hard philology.

If you can only give me one thing

Not the questions — the payload. Specifically:

model- the full

messages/inputarray - tool settings (anything like

tools,tool_choice, “web_search”) max_output_tokens

Even if you can’t find “the JSON”, many plugins log something like it in:

- WP debug log (

WP_DEBUG_LOG) - your server’s PHP error log

- the plugin’s own “request log”

- browser dev tools (Network tab) if it calls your server endpoint

If you paste that payload (redact keys), I’ll tell you exactly where the 64k is coming from in one pass.

Second answer

Your conclusions are basically right — and the screenshot explains why the bill blew up.

What that config is really doing (the expensive bits)

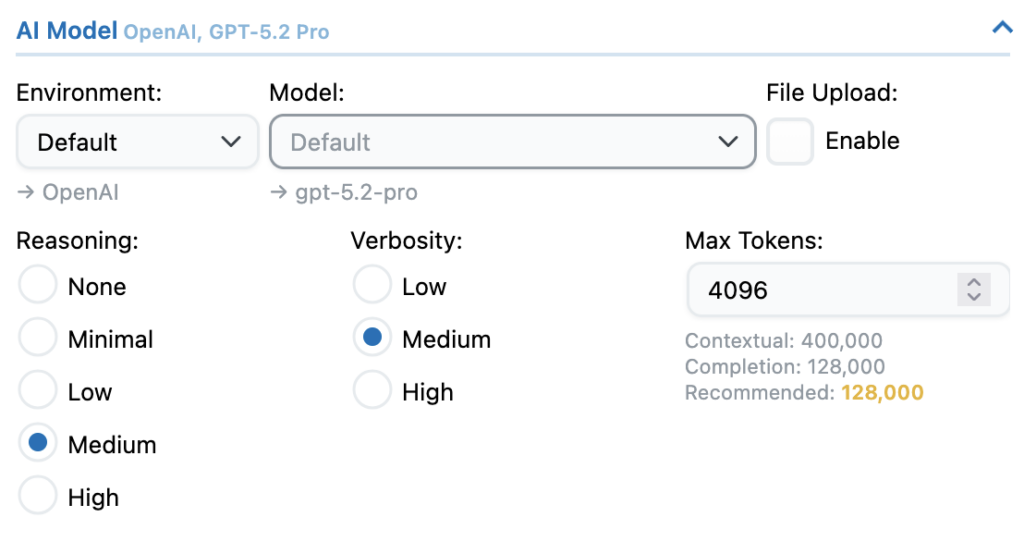

From the panel you posted:

- Model:

gpt-5.2-pro - Reasoning: Medium

- Verbosity: Medium

- Max tokens: 4096

- Context window: 400,000 (!!)

- Web search: Enabled

None of those limit input. They only cap output.

So if the plugin sends:

- your long system prompt

- full prior conversation

- web-search results (often thousands of tokens per call)

…the model happily ingests tens of thousands of tokens before it ever thinks about producing up to 4096 output tokens.

That’s exactly what your spend graph shows.

Why third-party tools feel “cheap”

You’ve put your finger on it:

if third party services are limiting their AI costs, they are doing so by removing the potency of the tool

Yes. Almost always they:

- truncate history aggressively

- summarise context instead of passing it verbatim

- disable browsing except on demand

- cap outputs at a few hundred tokens

- use cheaper models

- cache answers

- sometimes lie a bit about “AI-powered” depth

That’s the only way to make unit economics work.

Why your use case is worst-case for API billing

Your place-name analysis prompt:

- encourages long, structured answers

- encourages source citation

- triggers web search

- produces outputs worth thousands of tokens

- and then those outputs get recycled into the next input

That is exactly how you hit 40k–80k input tokens without noticing.

Your instinct about Custom GPTs is sensible

For this application:

✔ Custom GPT inside ChatGPT

- Fixed price (Plus/Team)

- Browsing + citations included

- No per-token anxiety

- No plugin plumbing

- No accidental 64k inputs

✖ API + WP plugin

- You pay for every mistake

- You must engineer token hygiene

- Hard to justify unless:

- high traffic or

- monetised or

- doing something ChatGPT UI cannot

For exploratory, scholarly, or boutique tools: ChatGPT wins.

If you do keep the API path open (minimal viable fixes)

If you want to keep experimenting without haemorrhaging money:

- Turn web search OFF by default

- Add a toggle: “Use sources (costly)”

- Hard-trim conversation

- Last user turn + last assistant turn only

- Summarise, don’t resend

- Store a rolling 200–300 token summary

- Drop Pro

- Use non-Pro unless you can justify it

- Lower expectations

- 300–600 token outputs for routine queries

Bottom line (plain speaking)

- Nothing is “wrong” with OpenAI pricing — it’s honest pricing.

- What’s expensive is naively wiring powerful models into chat UIs.

- Most commercial tools survive by blunting the knife.

- For your current goals, a Custom GPT is the rational choice.

If later you want:

- a paid place-name research tool,

- batch processing of names,

- GIS-linked analysis,

- or something ChatGPT can’t host,

then the API makes sense — but only with ruthless token discipline.

If you want, next step could be:

- a leaner system prompt that keeps your scholarly standards but costs 1/10th, or

- a decision tree: ChatGPT vs API vs hybrid, based on use case.

Third answer

You’re asking the right question, and it’s one many people dodge.

Below is a clear-eyed breakdown of what people actually use AI for, what it costs, and what the user is really paying for — stripped of hype.

1. The three cost drivers (this explains everything)

Forget “AI” as a single thing. Cost is driven by three levers:

- Tokens – how much text goes in and out

- Compute intensity – reasoning depth, multimodality, search/tools

- Product wrapping – UI, hosting, caching, support, margin

Most “cheap” AI tools are cheap because they minimise (1) and (2) and hide it behind (3).

2. Typical use cases, costs, and where the value actually lies

A. Text chat / Q&A (most tools)

Examples

- Customer support bots

- “Ask a question” widgets

- Writing assistants

Actual cost

- $0.001–$0.02 per interaction (if done sensibly)

- Often <300 tokens total

What the user pays

- Convenience

- Speed

- Avoiding a human

Hidden reality

- Heavily truncated prompts

- No memory

- No browsing

- Often wrong but “confident enough”

Value add

- Low per interaction

- Scales well

- Works only because expectations are low

B. Image generation

Examples

- Marketing images

- Concept art

- Thumbnails

Actual cost

- $0.02–$0.20 per image (depending on model & resolution)

What the user pays

- Not hiring a designer yet

- Iteration speed

Hidden reality

- User does the creative direction work

- Many images are discarded

- Legal/IP risk still unclear in some contexts

Value add

- Medium

- Real for ideation, weak for finished work

C. Video generation (current hype)

Examples

- Short marketing clips

- Social content

- Explainers

Actual cost

- $0.50–$5+ per clip (and rising fast)

What the user pays

- Novelty

- Speed over quality

Hidden reality

- Output often unusable without editing

- Style coherence is fragile

- Costs explode at scale

Value add

- Low-to-medium

- Mostly promotional, not operational

D. Search + synthesis (your use case)

Examples

- Research assistants

- Legal/academic analysis

- Due diligence

- Place-name etymology (exactly this)

Actual cost

- $0.50–$5 per good answer

- More if browsing + citations are real

What the user pays

- Time compression

- Cognitive labour

- Access to synthesis, not facts

Hidden reality

- This is where AI is genuinely doing work

- It’s expensive because it replaces skilled human reasoning

Value add

- High

- But hard to monetise casually

E. Automation / agents (the serious stuff)

Examples

- Data processing

- Report generation

- GIS / code / analysis pipelines

- Decision support

Actual cost

- $0.10–$10+ per run

- Often amortised over real outcomes

What the user pays

- Reduced labour

- Reduced error

- Repeatability

Hidden reality

- Requires engineering discipline

- Not “plug and play”

- Fails silently if badly designed

Value add

- Very high

- This is where AI earns its keep

3. Why your Fernylea example feels overpriced (but isn’t)

You weren’t paying for:

- “A chat”

- “Some words”

You were paying for:

- Long-context reasoning

- Cross-linguistic synthesis

- Source-aware analysis

- Structured academic-style output

In human terms: 30–60 minutes of a competent researcher’s work.

At $2–$4, that’s actually cheap — it just doesn’t scale well as a casual widget.

4. Why monetisation is hard (your key discomfort)

AI adds real value when:

- The task is expensive without AI

- The output is reused, sold, or acted on

- Accuracy matters more than vibes

AI struggles when:

- The task is “nice to have”

- The user expects it to be free

- The output is one-off and bespoke (like your queries)

That’s why:

- Serious AI is hidden inside workflows

- Trivial AI is cheap but shallow

- Most “AI startups” are wrappers with tight limits

5. Your implicit conclusion (and it’s correct)

“Unless I can monetise them big time…”

Yes. Or embed them deeply into something that already has value:

- A research service

- A consultancy

- A paid database

- A professional toolchain

Otherwise:

- Custom GPTs are rational

- API use is for products, not curiosity

- Token discipline is non-negotiable

Bottom line (no sugar-coating)

AI isn’t overpriced — casual use of powerful AI is.

Cheap AI survives by being weak.

Powerful AI survives by being rare, focused, and justified.

Your Fernylea example sits firmly in the “powerful but niche” category — which is why it feels uncomfortable when metered, and perfectly fine when bundled.

If you want, next we can:

- map your projects to where AI actually adds economic value, or

- sketch what a paid, sustainable version of your place-name work would even look like.

Switching the conversation to general and trivial uses of AI in areas such as image generation, video, etc. Can you create a summary of typical use cases and what they cost and what the user is actually paying? I’m struggling a little to understand how AI can add monetary value to an offering, even if I can see that the most powerful implementations are valuable (for serious applications).

Below is a clear-eyed breakdown of what people actually use AI for, what it costs, and what the user is really paying for — stripped of hype.

1. The three cost drivers (this explains everything)

Forget “AI” as a single thing. Cost is driven by three levers:

- Tokens – how much text goes in and out

- Compute intensity – reasoning depth, multimodality, search/tools

- Product wrapping – UI, hosting, caching, support, margin

Most “cheap” AI tools are cheap because they minimise (1) and (2) and hide it behind (3).

2. Typical use cases, costs, and where the value actually lies

A. Text chat / Q&A (most tools)

Examples

- Customer support bots

- “Ask a question” widgets

- Writing assistants

Actual cost

- $0.001–$0.02 per interaction (if done sensibly)

- Often <300 tokens total

What the user pays

- Convenience

- Speed

- Avoiding a human

Hidden reality

- Heavily truncated prompts

- No memory

- No browsing

- Often wrong but “confident enough”

Value add

- Low per interaction

- Scales well

- Works only because expectations are low

B. Image generation

Examples

- Marketing images

- Concept art

- Thumbnails

Actual cost

- $0.02–$0.20 per image (depending on model & resolution)

What the user pays

- Not hiring a designer yet

- Iteration speed

Hidden reality

- User does the creative direction work

- Many images are discarded

- Legal/IP risk still unclear in some contexts

Value add

- Medium

- Real for ideation, weak for finished work

C. Video generation (current hype)

Examples

- Short marketing clips

- Social content

- Explainers

Actual cost

- $0.50–$5+ per clip (and rising fast)

What the user pays

- Novelty

- Speed over quality

Hidden reality

- Output often unusable without editing

- Style coherence is fragile

- Costs explode at scale

Value add

- Low-to-medium

- Mostly promotional, not operational

D. Search + synthesis (your use case)

Examples

- Research assistants

- Legal/academic analysis

- Due diligence

- Place-name etymology (exactly this)

Actual cost

- $0.50–$5 per good answer

- More if browsing + citations are real

What the user pays

- Time compression

- Cognitive labour

- Access to synthesis, not facts

Hidden reality

- This is where AI is genuinely doing work

- It’s expensive because it replaces skilled human reasoning

Value add

- High

- But hard to monetise casually

E. Automation / agents (the serious stuff)

Examples

- Data processing

- Report generation

- GIS / code / analysis pipelines

- Decision support

Actual cost

- $0.10–$10+ per run

- Often amortised over real outcomes

What the user pays

- Reduced labour

- Reduced error

- Repeatability

Hidden reality

- Requires engineering discipline

- Not “plug and play”

- Fails silently if badly designed

Value add

- Very high

- This is where AI earns its keep

3. Why your Fernylea example feels overpriced (but isn’t)

You weren’t paying for:

- “A chat”

- “Some words”

You were paying for:

- Long-context reasoning

- Cross-linguistic synthesis

- Source-aware analysis

- Structured academic-style output

In human terms: 30–60 minutes of a competent researcher’s work.

At $2–$4, that’s actually cheap — it just doesn’t scale well as a casual widget.

4. Why monetisation is hard (your key discomfort)

AI adds real value when:

- The task is expensive without AI

- The output is reused, sold, or acted on

- Accuracy matters more than vibes

AI struggles when:

- The task is “nice to have”

- The user expects it to be free

- The output is one-off and bespoke (like your queries)

That’s why:

- Serious AI is hidden inside workflows

- Trivial AI is cheap but shallow

- Most “AI startups” are wrappers with tight limits

5. Your implicit conclusion (and it’s correct)

“Unless I can monetise them big time…”

Yes. Or embed them deeply into something that already has value:

- A research service

- A consultancy

- A paid database

- A professional toolchain

Otherwise:

- Custom GPTs are rational

- API use is for products, not curiosity

- Token discipline is non-negotiable

Bottom line (no sugar-coating)

AI isn’t overpriced — casual use of powerful AI is.

Cheap AI survives by being weak.

Powerful AI survives by being rare, focused, and justified.

Your Fernylea example sits firmly in the “powerful but niche” category — which is why it feels uncomfortable when metered, and perfectly fine when bundled.

If you want, next we can:

- map your projects to where AI actually adds economic value, or

- sketch what a paid, sustainable version of your place-name work would even look like.